Phil Byrd is one of the JOHN W BROWN's volunteers and he is currently a Masters degree candidate studying Museum Studies at the University of Maryland. He thesis project was to research, design and implement an exhibit on the ship. You can read what it was like for him below.

Last night I thought I was supposed to be nervous about opening my first exhibit, but I wasn’t. I thought that was odd, but I suppose I was confident about the work I had done and either way the exhibit is complete so I just had to make sure to be a good host. The experience of curating World War II through the eyes of Walter Olencz didn’t really hit me until there was a crowd in front of the exhibit and I saw people actually reading every word I put up.

It all started when I ruined someone’s picture, she was photographing something attached to a door that I opened as she snapped the picture. She then asked me the difference between a Liberty Ship and a Victory Ship, I explained the difference and it turns out her father sailed on both types of those ships. I asked a little more about her father, if she knew anything else about his career, as I customarily do with visitors, and she pulled out a folder full of high resolution copies of documents from World War II. Her name is Nancy Van Keuren and her father is Walter Olencz.

In that moment I decided that I needed to do an exhibit on Walter Olencz, or Walt, because of how complete a record Nancy has and because his story of very common and very untold. Most history exhibits are about the Captain in charge of the ship that did the thing or the business tycoon that funded the new way to do the whatever but Walt’s story is of a young son of Ukrainian immigrants traveling all over the world and going from a shipboard dishwasher to an unlicensed engine officer.

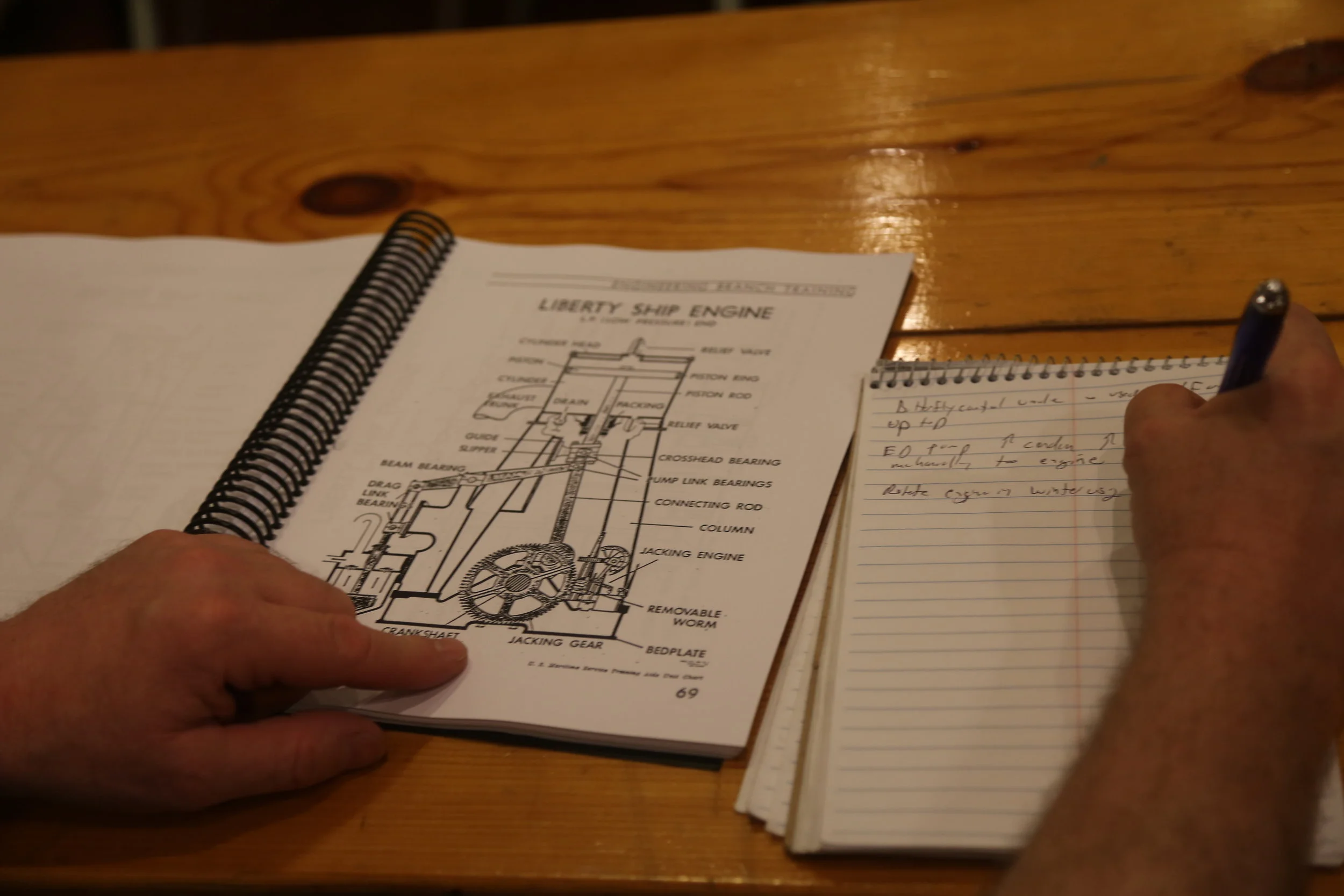

When I started doing research all I had were his documents that chronicled his Merchant Marine career which, to those outside the industry, might as well be written in Greek. I also didn’t have personal source material, his stories or correspondence, so I used several editorials from the 1940’s and oral histories about the World War II Merchant Marine to fill in the blank spaces between the documents. I also told a larger story using Walt’s experiences. It’s a story of ships built for war and used up until the 1990’s, of private shipping companies disputing pay with labor unions, of the Maritime Commission amassing the largest merchant fleet in the world.

At the end of World War II Liberty Ships alone made up 23% of all the shipping tonnage in the world.

When I submitted my paper the comments I received from the museum studies certificate board were essentially “this is a great narrative of a merchant mariner, but who is Walter Olencz?” I had been so research focused that I lost sight of the personal story that drives the exhibit! So I reached out and got some amazing quotes from Nancy as well as a doctor from Johns Hopkins, where Walt retired from. I bookended the exhibit with personal stories about Walt; you begin the exhibit by getting a sense of who he was, you look at his entire maritime career on a timeline, then you end with how working in engine rooms for five years prepared Walt to literally write the book on Kodak radiology equipment.

A couple more things I want to share about the exhibit.

When I scheduled the opening I was a bit selfish and picked the day that worked best for me without consulting anyone. Not surprisingly some people couldn’t make it, most notably Nancy. The Saturday before the opening I was finishing up and she came down to see the almost completed exhibit so I asked her to help me put up a couple pieces. Without realizing it, she put up the piece with a picture of her father, Walt, in his WWII uniform and a story from an email she wrote to me about her father. When she saw she story she emailed me was going up permanently in the exhibit I could sense her heart swelling with pride and love which really showed me what this museum career of mine is all about: making personal connections with the past to uncover stories that haven’t been told. The future of museums is in people’s attics and basements.

This last little part deals with the MA thesis I’m writing and how this lesson shaped my thinking about exhibiting authenticity. So when I was doing research and trying to find pictures of the ships Walt sailed on the hardest one to nail down was the SS Conastoga. It was impossible to find a picture of the ship during WWII and I was almost thinking of cutting this ship from the exhibit and focusing on a different vessel. The only picture I could find was from 1954 after it was renamed the SS Hess Fuel and lengthened to accommodate more fuel (it was a T2-SE-A1 tanker). I thought about putting up a photograph of a tanker of the same class but I thought: “if Walt saw the exhibit with some other tanker he’d say ‘I sailed on one of those’ but if he saw the picture of the SS Hess Fuel he’d say ‘that was MY ship.’” Even though the picture of the generic T2 would be historically authentic to the time and context, the personal connection with that specific ship, and it’s post war life, was a more compelling and interesting story.

Ok I’m done now. I’d like to that Nancy Van Keuren for helping me with everything. Ashley Minner who gave me tips on making the physical display. All my professors for guiding my research. Walt’s family and everyone for coming to the opening and all the compliments. And my sweet Bassett Hound, Daphne, who would always let me know when I was sitting at the computer too long and should take her for a walk.